Role Performer, Role, Function, and System Names

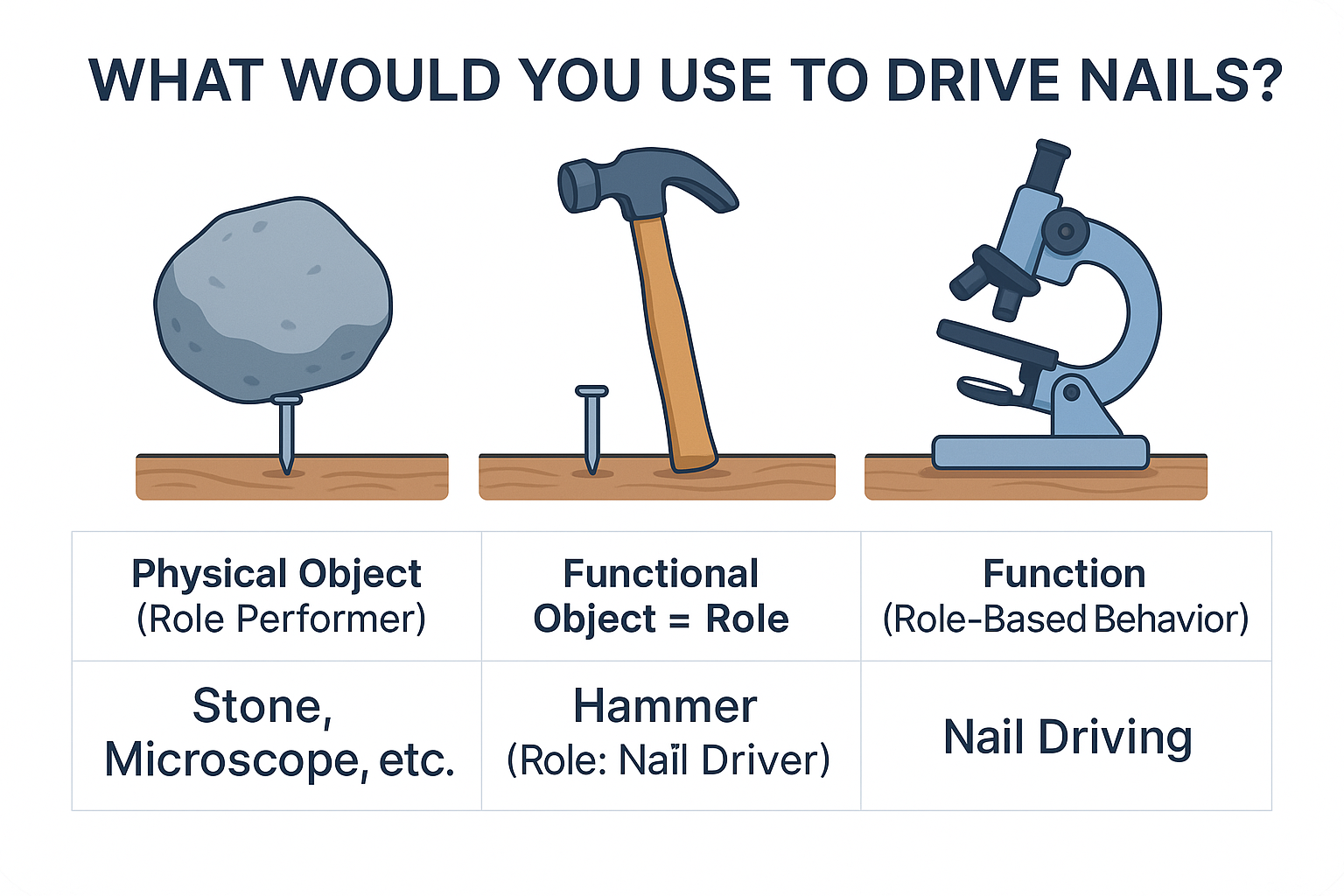

In the previous section, we already discussed the difference between a physical object, a functional object, and functional (or role-based) behavior. For example, a physical object is a microscope[1] or a stone. These objects can play different roles and perform different functions assigned to them by someone. In our example, the functional object or role is the "nail driver." In culture, this role is commonly called a "hammer." The function, or functional or role-based behavior, is driving nails.

As we mentioned earlier, each role is associated with culturally conditioned[2] behavior and a corresponding, culturally established name. Everyone understands what the role "hammer" is and its behavior—driving nails. The physical item that can become a hammer[3] can be different.

This way of thinking—naming things by their main function[4]—significantly reduces the brain's computational load. That is, we first consider actions (behavior and other activities), and only then identify the physical objects that can perform these actions. Cultural conditioning allows us to reach agreements more quickly[5]: there's no need to call the functional object "the person who drives a car" every time. Instead, we can more quickly and concisely refer to this role as "driver"[6].

Here's a brief excerpt on this topic from the textbook "Systems Thinking":

"Systems are primarily considered as functional (role-based) objects at the moment when they perform their function—that is, when they are ready and operating. At this moment, they provide value to those who need that function. For example, an airplane, as a system, is first and foremost a role-based or functional object that enables flight, while transporting passengers and cargo through the air. The most common purpose or function of an airplane is to enable flight. This functionality is directly reflected in the system's name, 'airplane,' which combines 'air'—the medium in which it operates—and 'plane,' referring to the flat surfaces (wings) that generate lift for flight.

The main purpose of a pump is to pump. That's why, in culture, this product has acquired such a name. Manufacturers want to please their clients, so they name their products in a way that allows the client to quickly understand the benefit. Clients consciously (or intuitively) understand the desired function and get acquainted with manufacturers' products starting from their functional name[7]. Nevertheless, a system named by the manufacturer as "Pump NV-23"[8] may serve a different function for the client. For example, it might be used to inject antifreeze. In this case, the client's request for a function has changed—they need a functional object: an antifreeze injector. Will the "Pump NV-23" work as an "antifreeze injector"? Perhaps it will.

So, a pump can be called an "antifreeze injector for the secondary cooling circuit" if its role is to inject antifreeze in the secondary circuit. The factory will sell the physical object "Pump NV-23"[9], but the buyer will use it in a different role (as an injector). This happens all the time. Without a usage context, it's "just a pump"—a structural object, with no environment. In the context of playing a role, it's a role-based object: "antifreeze injector for the secondary cooling circuit." Outside the context of engineering skills, Masha is just Masha—she can be many things. Similarly, a microscope can be used to view small objects, crack nuts, drive nails, or serve as a paperweight. Masha, too, can do many things. But at the moment she is performing the function of an engineer—engaging in role-based behavior—she will be called "engineer." And that's perfectly normal."

Thus, it's important to name systems according to their primary purpose[10], that is, by the roles assigned to them. These roles define the function. But sometimes the function is clear, while it's not so easy to name the role right away[11]. To easily find the name of a role, you need to have a broad activity-based perspective.

When we name a system "microscope," we primarily mean that it allows us to "look at small objects" at the moment when it is fully assembled and working. If we thought we would use this object to drive something in, we would say that the physical object "Microscope MP-2" will play the role of "hammer" and perform the function of driving or hammering.

And if someone suddenly declares a person to be a system, usually there's little that can be said immediately about their function in the surroundings. A person is a multifunctional object—they can perform many actions, and a person can be considered as a biological body (from this perspective, for example, medicine views people). We discussed in the previous section that a person can play a variety of roles. Therefore, you always have to analyze people's role-based behavior or functions separately and specifically. But thinking about people in roles and about a microscope-in-a-role works the same way![12]

If you find it difficult to sort out all these concepts, or you don't understand the importance of such distinctions for project work, it means you have gaps in your knowledge of ontology. To master systems thinking, you need to have a type classifier/cognitive type machine in your mind[13]. If you're having trouble with this, we recommend taking the "Rational Work" course.

Although, when we say "microscope," we primarily mean the role "microscope." But we also use this word to refer to the physical item commonly called a microscope. The difference can only be understood from the context of the discussion. It's great if you've picked up on this duality, just as with a hammer. A systems-oriented person understands this distinction well. But it's best to start with a stone. ↩︎

Or determined by cultural norms and rules, i.e., accepted in culture, in norms of behavior, usage, etc. ↩︎

That is, play the role of a hammer. Note that the reasoning is exactly the same if we were talking about the role of a manager being played by John Doe or Jane Doe. ↩︎

Or by their role-based behavior. ↩︎

Although not all established names for objects follow this principle. Sometimes ancient names have unclear origins and often refer not to the role/function, but to the form or something else. As a rule of thumb, when a team is developing a system, it's best to look for a role—and an indication of the function or actions of that role—in the name, rather than the physical object representing the system. ↩︎

Similarly, it was previously suggested not to call the functional object "nail driver," but to use the role name "hammer" instead. ↩︎

Products may have alternative names; for example, airplanes are named after great individuals. ↩︎

Here, we're talking about the physical object—"Pump NV-23," which can perform the function of pumping and play the role of a pump. ↩︎

This product was designed to play the role of a pump, i.e., to perform the function of pumping. ↩︎

Keep in mind that in established object names, this rule may not always be followed, but in your own projects, you'll save a lot of time if you stick to it. You'll be able to reach agreements faster and understand client requests and your product more clearly. For more on naming systems, see Section 5 of the online course "Systems Thinking." ↩︎

It's easy to realize you need the function "driving nails," and therefore the role is "nail driver." But to come up with the role name "hammer" requires a broader activity-based perspective. While "hammer" is fairly straightforward, try naming project roles at an aircraft factory or the names of airplane subsystems. ↩︎

Systems thinking begins with considering systems as role-based (functional) objects that behave in some way in their environment. That is, we first look at the performed or required function, the played role, or the purpose. Only after that do we deal with the structure or the physical object that will play the identified role. ↩︎

Recall that this is the ability to track the types of concepts being used and not to confuse, for example, a role and a performer, a system and a process, a function and a structure, etc. ↩︎