Systems Approach 2.0

In the classic systems approach, systems were viewed as material objects possessing three properties: integrity (of a system), emergence, and nestedness[1]. However, these systems were considered as ideal physical objects, entirely disconnected from human interests. The connection to human interests emerged in what is known as systems approach 2.0, which is based on entirely different systems methodologies compared to the first generation[2].

Systems approach 2.0 does not reject the classic properties of a system introduced in the first generation. These are all necessary conditions for its existence, but they are no longer sufficient. In the modern interpretation, the concept of "system" acquires new additional properties that arise from a subjective perspective on the system.

As we mentioned earlier, the classic approach is more abstract and considers ideal objects, while the second-generation systems approach is pragmatic, working with objects that are needed by someone for a particular reason or that somehow affect specific people.

Systems approach 2.0 is not used when you simply want to talk about a table, a clock, or a car without reference to a real project. That is more like discussing ideal objects in a mental space, and often, in such conversations, there is no specific physical object in mind that is needed by particular people in specific projects.

Systems thinking comes into play when we talk about systems like "office desk," "wristwatch," or "passenger vehicle." In these cases, at least, we can discuss the interests and relevant roles of those who want something from these systems. Based on this, the system, its boundaries, and how it will be used are defined.

In systems approach 2.0, all project roles that in some way influence the system, or people in certain roles who may be affected by it, are considered stakeholders. The sum of all interests of project roles determines what the system will be, its function, what it will consist of, and so on.

The key mental technique here is: "No interests—no system." For example, an automotive corporation develops a passenger vehicle taking into account the possible interests of potential clients in the roles of driver, passenger, user, owner, pedestrians, regulatory authorities, environmental advocates, and so on. Whether it will be a passenger or a cargo vehicle, what kind of engine it will have, or its payload capacity—all depend on the interests of the stakeholders.

Each interest that is taken into account determines what the vehicle should be. Without an environmental interest, there would be no need to install an exhaust gas purification subsystem that meets Euro-6 standards. By adding such a subsystem to the vehicle, the manufacturer has changed the system's structure.

Everything installed in a passenger vehicle is a response to some project role's interest that the automaker decided to address. The "passenger vehicle" system will be successful if the interests of all stakeholders (project roles) are addressed (satisfied).

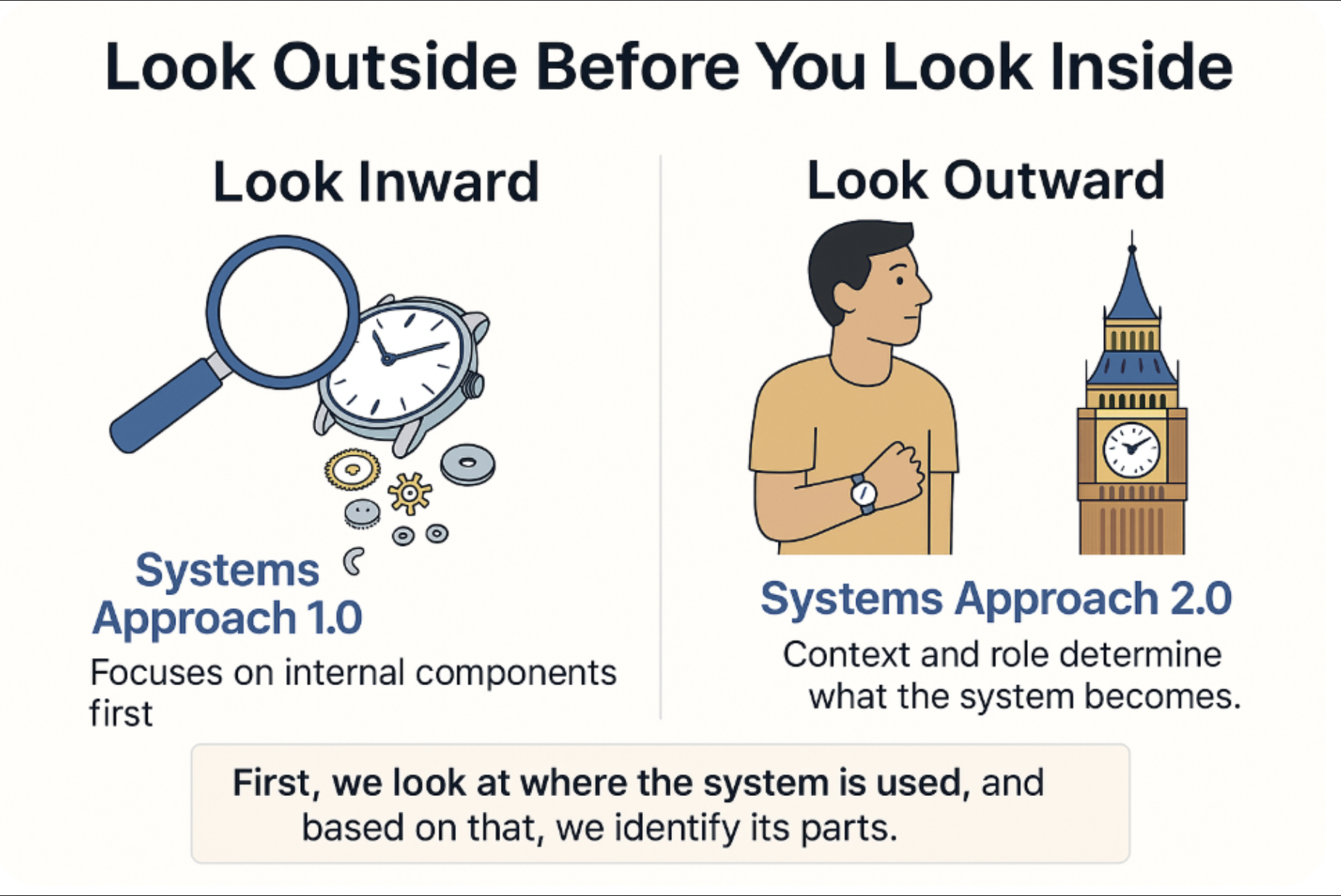

Let's now discuss this systems thinking technique: first, look "outside," and only then "inside" the system.

The interaction between the system and project roles determines its boundary (integrity), function, and structure. Therefore, the discussion of a system does not begin with its internal structure, but with an understanding of its environment. That is, which supersystem the system belongs to, who needs it and what these stakeholders require, what problems and interests they have regarding the system. This leads to an important systems principle: always start by looking outside the system, and only then look inside.

For example, in the classic consideration of the "clock" system, a person would start by examining the system's properties and focus inward, discussing what it consists of. In the modern approach, you must start by looking outside the system—considering which supersystem the clock is part of, who needs it, and how it is used.

After such consideration, you understand whether you are talking about a wristwatch, a cuckoo clock, or a tower clock. The structure of each of these clocks will be different. Without compiling a list and understanding the interests of the relevant stakeholders, it is impossible to discuss the system's structure.

Thus, in systems approach 2.0, systems not only possess the properties of integrity (of a system), emergence, and nestedness, but their important property is that they depend on stakeholders (project roles). The success of the system depends on addressing the interests of project roles, so the analysis begins with the environment: first, look outside, and only then inside the system.

Do not confuse "nestedness" and "hierarchy." The latter may appear in descriptions of first-generation system properties, but this is incorrect. Hierarchy is a broader principle than nestedness. Nestedness is a specific case of hierarchy, meaning not every hierarchy implies nestedness. For example, a supervisor and a subordinate represent a hierarchy, but not nestedness. ↩︎

In both the first and second generations of the systems approach, there are various systems methodologies. Each has its own set of concepts and thinking techniques. But their common distinguishing feature is that, in addition to the concept of "system," each also uses the concept of "role," or "stakeholder," or "interested parties." One such second-generation systems methodology is the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ). ↩︎